Room 1

THE PALACE OF ARNOLFO

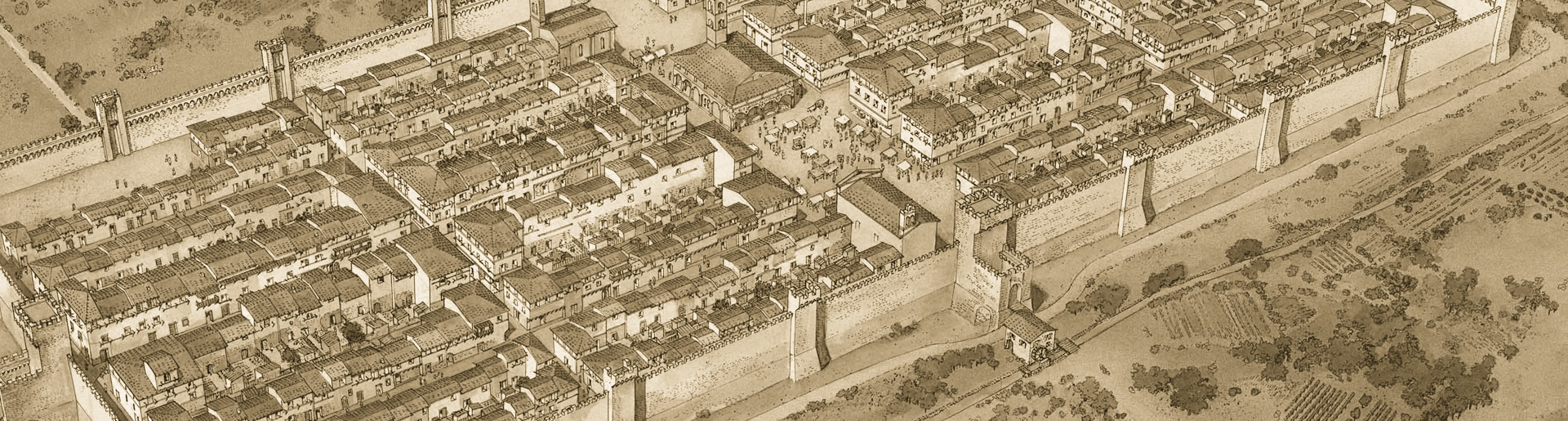

In this room the three construction stages of the Palazzo are illustrated, beginning in 1299, the year building started.

It was the seat of the administration of power, first by the Podestà and later by the Vicar.

The bell tower became an urban landmark, essential for marking the hours of the working day and the citizens’ daily routine.

After being the seat of the municipal offices, it became the venue of the New Lands Museum in 2013.

Insights

THE PALACE OF ARNOLFO

Following restoration work in 1934, the palace was commonly referred to by the inhabitants of San Giovanni as ‘Palazzo di Arnolfo’. The attribution of the project to Arnolfo di Cambio, in truth, accords with a historical tradition dating back to Giorgio Vasari who, in his Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects, attributed the design of the building and the entire township to the famous architect, asserting that, as a result of this undertaking, Arnolfo di Cambio – a native of Colle Val d’Elsa – was awarded the privilege of Florentine citizenship:

The Florentines, in the meanwhile, wishing to build walls in the Valdarno di Sopra round Castello di San Giovanni and Castel Franco, for the convenience of the city and of their victualling by means of the markets, Arnolfo made the design for them in the year 1295, and satisfied them in such a manner, as well in this as he had done in the other works, that he was made citizen of Florence.

As much as Vasari’s hypothesis is extremely appealing in attributing Castel San Giovanni a total Florentine filiation, historians agree that there is no documentary evidence of this while what can be affirmed with some certainty is that if he had indeed designed the plan of the new town and the civic palace, he could hardly have personally followed the construction phases. In fact, we know that Arnolfo died between 1302 and 1310, while the palace was finished several years later. In any case, the building was erected between the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth century and, like all civic palaces in newly founded centres, it was planned with precise political purposes in mind: functions that were renewed over the centuries; so much so that until the birth of the museum, it housed the municipal offices, representing the nerve centre of life in San Giovanni Valdarno. Even today, the building is to all intents and purposes a speaking symbol of the city. In the face of what can be defined as a multi-secular continuity of functions, it is nevertheless necessary to remember that the current appearance of the building is not the original one; rather, it is the result of various interventions, renovations and extensions that, as we shall see, have taken place over the centuries, profoundly transforming its layout and proportions, which were originally calibrated in relation to the structure of the urban layout.

(The text is taken from the museum guide, edited by Claudia Tripodi and Valentina Zucchi, Sagep, 2024)