The emergence of these New Lands was not just a feature of Italy but also of numerous other countries in Europe from the year 1000 onwards.

From French bastides – built basically as military fortifications – to English abbeys, which gathered together religious communities, this room provides an overview of the situation in 11th-century Europe, introducing the developments that would affect Tuscany from the 12th century until the mid-14th century.

The demographic growth that marked the period defined by historiography as the ‘long thirteenth century’ in a large part of Europe, and which began at the end of the previous century and lasted until the beginning of the following century, also offered the opportunity for a change of scale in the planning of new settlements whose capacity for population could grow to a respectable size. This gave rise not only to castles, but also to built-up centres and even to towns. Indeed, the population surplus produced even highly populated settlements in south-western France, Eastern Germany and the Iberian peninsula where their names (Villefranche, Freiburg, Salvatierra, etc.) still bear the memory of the prerogatives, tax immunities and personal freedoms offered to the new inhabitants. These were initiatives taken by sovereigns, powerful local lords, monasteries and knightly orders: Kings of Navarre or Aragon, Counts of Toulouse, Angevins, Cistercians, Templars and Teutonic Knights to name but a few.

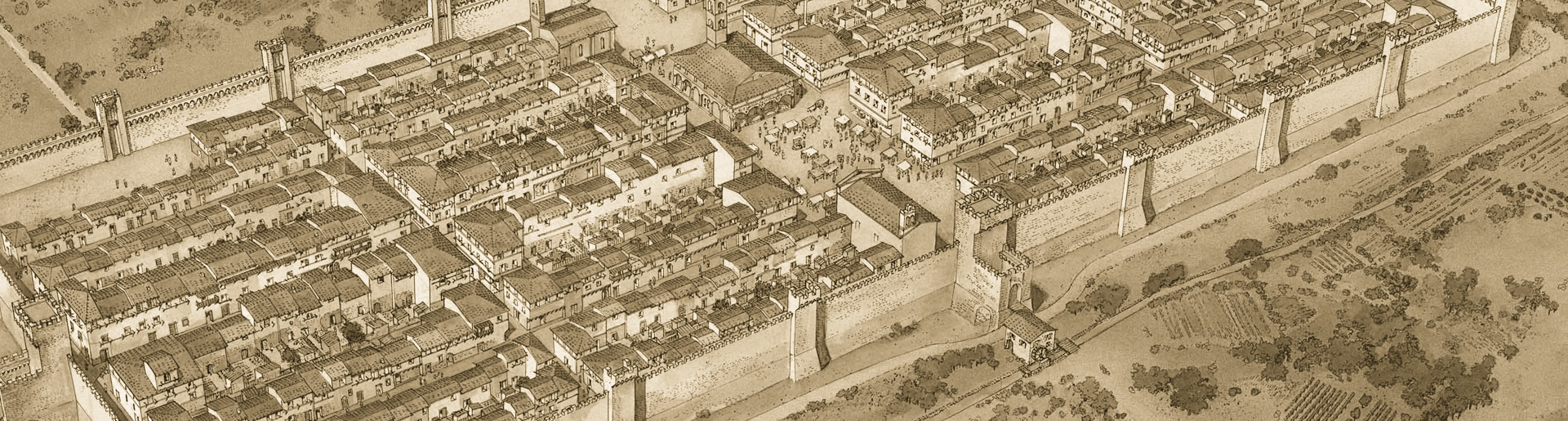

The wave of new foundations that had swept through much of Europe did not stop at the Alps. In the Italian peninsula, particularly in the central and northern area, the role of promoting new centres during the thirteenth century was taken on by municipal institutions that had, first and foremost, the evident aim of consolidating the city’s dominion over the countryside. This was, on closer inspection, a significant change in perspective compared to the logic that had overseen the birth and spread of the castles and fortified villages created on the initiative of the seigniory.

Indeed, the action of the city communes was no longer limited to concentrating individuals and families in one place, as the lords did to keep their fideles bound: on the contrary, these initiatives were based on the promise of enfranchisement and liberation from all feudal bonds for those who decided to move to the new centres. This explains the names chosen here too for the new settlements: Castelfranco, Villafranca or Borgo Franco manifested the political project envisaged for those who chose to live within the walls that were being erected. For the city municipalities, the foundation of new settlements was thus a further instrument for the realisation of effective hegemony over entire counties, for the implementation of control over the population but also over centres, markets, productive structures, roads and all other types of resources: in short, dominion over a territory, at least initially, circumscribed by the limits of the city’s jurisdiction over the counties.

Thus, while the great monarchies such as the Iberian, French and English had begun to structure their territories into real kingdoms, in the Italian peninsula, the Comuni went in the same direction, albeit on a relatively smaller scale, embarking on the first, sometimes uncertain and not always evident, steps towards the construction of a city state.

(The text is taken from the museum guide, edited by Claudia Tripodi and Valentina Zucchi, Sagep, 2024)

The New Lands Museum

We firmly believe that the internet should be available and accessible to anyone, and are committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of circumstance and ability.

To fulfill this, we aim to adhere as strictly as possible to the World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (WCAG 2.1) at the AA level. These guidelines explain how to make web content accessible to people with a wide array of disabilities. Complying with those guidelines helps us ensure that the website is accessible to all people: blind people, people with motor impairments, visual impairment, cognitive disabilities, and more.

This website utilizes various technologies that are meant to make it as accessible as possible at all times. We utilize an accessibility interface that allows persons with specific disabilities to adjust the website’s UI (user interface) and design it to their personal needs.

Additionally, the website utilizes an AI-based application that runs in the background and optimizes its accessibility level constantly. This application remediates the website’s HTML, adapts Its functionality and behavior for screen-readers used by the blind users, and for keyboard functions used by individuals with motor impairments.

If you’ve found a malfunction or have ideas for improvement, we’ll be happy to hear from you. You can reach out to the website’s operators by using the following email

Our website implements the ARIA attributes (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) technique, alongside various different behavioral changes, to ensure blind users visiting with screen-readers are able to read, comprehend, and enjoy the website’s functions. As soon as a user with a screen-reader enters your site, they immediately receive a prompt to enter the Screen-Reader Profile so they can browse and operate your site effectively. Here’s how our website covers some of the most important screen-reader requirements, alongside console screenshots of code examples:

Screen-reader optimization: we run a background process that learns the website’s components from top to bottom, to ensure ongoing compliance even when updating the website. In this process, we provide screen-readers with meaningful data using the ARIA set of attributes. For example, we provide accurate form labels; descriptions for actionable icons (social media icons, search icons, cart icons, etc.); validation guidance for form inputs; element roles such as buttons, menus, modal dialogues (popups), and others. Additionally, the background process scans all the website’s images and provides an accurate and meaningful image-object-recognition-based description as an ALT (alternate text) tag for images that are not described. It will also extract texts that are embedded within the image, using an OCR (optical character recognition) technology. To turn on screen-reader adjustments at any time, users need only to press the Alt+1 keyboard combination. Screen-reader users also get automatic announcements to turn the Screen-reader mode on as soon as they enter the website.

These adjustments are compatible with all popular screen readers, including JAWS and NVDA.

Keyboard navigation optimization: The background process also adjusts the website’s HTML, and adds various behaviors using JavaScript code to make the website operable by the keyboard. This includes the ability to navigate the website using the Tab and Shift+Tab keys, operate dropdowns with the arrow keys, close them with Esc, trigger buttons and links using the Enter key, navigate between radio and checkbox elements using the arrow keys, and fill them in with the Spacebar or Enter key.Additionally, keyboard users will find quick-navigation and content-skip menus, available at any time by clicking Alt+1, or as the first elements of the site while navigating with the keyboard. The background process also handles triggered popups by moving the keyboard focus towards them as soon as they appear, and not allow the focus drift outside it.

Users can also use shortcuts such as “M” (menus), “H” (headings), “F” (forms), “B” (buttons), and “G” (graphics) to jump to specific elements.

We aim to support the widest array of browsers and assistive technologies as possible, so our users can choose the best fitting tools for them, with as few limitations as possible. Therefore, we have worked very hard to be able to support all major systems that comprise over 95% of the user market share including Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Apple Safari, Opera and Microsoft Edge, JAWS and NVDA (screen readers).

Despite our very best efforts to allow anybody to adjust the website to their needs. There may still be pages or sections that are not fully accessible, are in the process of becoming accessible, or are lacking an adequate technological solution to make them accessible. Still, we are continually improving our accessibility, adding, updating and improving its options and features, and developing and adopting new technologies. All this is meant to reach the optimal level of accessibility, following technological advancements. For any assistance, please reach out to