To become a terrazzano, that is, an inhabitant of a new land, meant building one’s own house. The time permitted was extremely short so the technique of pisé was used: sand pressed into formworks (moulds) that made the foundations of the houses. The houses, reproduced in the room with the help of models, consisted of a workshop on the ground floor, a first floor as living area and a kitchen garden with a well shared with another plot. They could also be enlarged: wealthy people usually occupied several adjacent lots, as in the case of Palazzo Salviati, known as Il Palazzaccio.

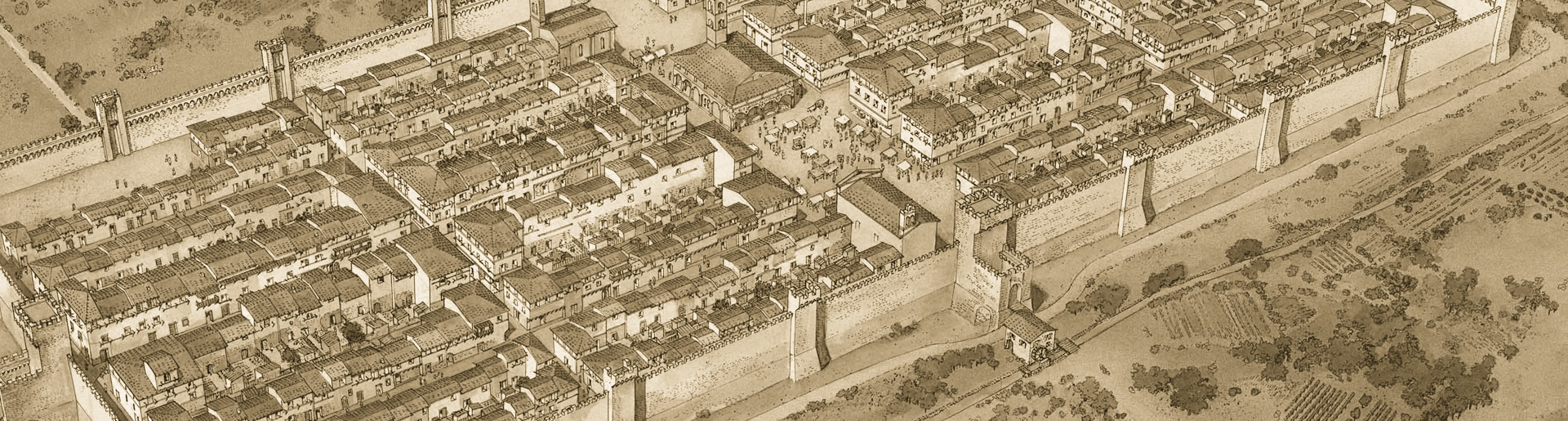

The construction of San Giovanni was progressively defined, and it is likely that by the second half of the fourteenth century, as in Scarperia and Firenzuola, the fortification works were still far from being completed, and were still replaced by wooden palisades. According to Francesco Gherardi Dragomanni, the nineteenth-century author of the Memorie della terra di San Giovanni nel Valdarno Superiore, in 1352, a large part of the walls was still ‘disconnected and in ruins.’ A few years after the foundation, taking advantage of a lull in the conflict with the lords of Valdarno, Florence had begun to fortify the town of San Giovanni with works that lasted until 1363. The archaeological investigations conducted on the remains speak of rubble masonry, with a facing in pebbles and small river stones of uniform size, placed on parallel courses and joined by strong mortar. It is therefore plausible to assume that the constructions built against the walls date back to at least the end of the fifteenth century or at least to a time when the walls had lost their defensive military value.

(The text is taken from the museum guide, edited by Claudia Tripodi and Valentina Zucchi, Sagep, 2024)

Becoming an inhabitant of a Terra Nuova brought with it a set of new elements but also obligations such as that of building one’s own house. In San Giovanni, houses were arranged in rows, with fronts lined up on the main street, back-to-back, separated by narrower streets, also called chiassi, punctuated by bridges and overhead galleries. The inhabitants of a Terra Nuova were required to build their dwellings on the allotted building lot in just under a year. The short time available and the basic knowledge of building techniques drove most builders to the use of sabbione – a strong yellow clay, abundantly present on site – and to the adoption of the technique of pisé (beaten earth) and unfired bricks. The procedure was quite simple: the foundations, no more than 30 centimetres deep (for which river pebbles and mortar were used), were quickly made, and formwork made of wooden planks, interspersed with vertical piles, was placed on them, with clay poured in, gradually wetting it and compacting it with large wooden pestles. This was done by progressively moving the planks up to the desired height. Over time, building techniques changed and mixed walls of pebbles and bricks or reused materials were built. The outer surfaces of the earthen walls were smoothed with milk of lime for protection; in areas most exposed to the weather, where this smoothing proved insufficient, it soon became necessary to resort to brick lining.

The façade of the house on the first floor might have an overhang, made of wood or wattle, resting on beams. These overhangs were progressively replaced by masonry structures, and led to the creation of proper porticos, which can still be seen today along the main street. The house facing the street left space in the remaining part of the allotted plot for a vegetable garden, where there was often a well, located between two neighbouring properties and shared.

(The text is taken from the museum guide, edited by Claudia Tripodi and Valentina Zucchi, Sagep, 2024)

The New Lands Museum

We firmly believe that the internet should be available and accessible to anyone, and are committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of circumstance and ability.

To fulfill this, we aim to adhere as strictly as possible to the World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (WCAG 2.1) at the AA level. These guidelines explain how to make web content accessible to people with a wide array of disabilities. Complying with those guidelines helps us ensure that the website is accessible to all people: blind people, people with motor impairments, visual impairment, cognitive disabilities, and more.

This website utilizes various technologies that are meant to make it as accessible as possible at all times. We utilize an accessibility interface that allows persons with specific disabilities to adjust the website’s UI (user interface) and design it to their personal needs.

Additionally, the website utilizes an AI-based application that runs in the background and optimizes its accessibility level constantly. This application remediates the website’s HTML, adapts Its functionality and behavior for screen-readers used by the blind users, and for keyboard functions used by individuals with motor impairments.

If you’ve found a malfunction or have ideas for improvement, we’ll be happy to hear from you. You can reach out to the website’s operators by using the following email

Our website implements the ARIA attributes (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) technique, alongside various different behavioral changes, to ensure blind users visiting with screen-readers are able to read, comprehend, and enjoy the website’s functions. As soon as a user with a screen-reader enters your site, they immediately receive a prompt to enter the Screen-Reader Profile so they can browse and operate your site effectively. Here’s how our website covers some of the most important screen-reader requirements, alongside console screenshots of code examples:

Screen-reader optimization: we run a background process that learns the website’s components from top to bottom, to ensure ongoing compliance even when updating the website. In this process, we provide screen-readers with meaningful data using the ARIA set of attributes. For example, we provide accurate form labels; descriptions for actionable icons (social media icons, search icons, cart icons, etc.); validation guidance for form inputs; element roles such as buttons, menus, modal dialogues (popups), and others. Additionally, the background process scans all the website’s images and provides an accurate and meaningful image-object-recognition-based description as an ALT (alternate text) tag for images that are not described. It will also extract texts that are embedded within the image, using an OCR (optical character recognition) technology. To turn on screen-reader adjustments at any time, users need only to press the Alt+1 keyboard combination. Screen-reader users also get automatic announcements to turn the Screen-reader mode on as soon as they enter the website.

These adjustments are compatible with all popular screen readers, including JAWS and NVDA.

Keyboard navigation optimization: The background process also adjusts the website’s HTML, and adds various behaviors using JavaScript code to make the website operable by the keyboard. This includes the ability to navigate the website using the Tab and Shift+Tab keys, operate dropdowns with the arrow keys, close them with Esc, trigger buttons and links using the Enter key, navigate between radio and checkbox elements using the arrow keys, and fill them in with the Spacebar or Enter key.Additionally, keyboard users will find quick-navigation and content-skip menus, available at any time by clicking Alt+1, or as the first elements of the site while navigating with the keyboard. The background process also handles triggered popups by moving the keyboard focus towards them as soon as they appear, and not allow the focus drift outside it.

Users can also use shortcuts such as “M” (menus), “H” (headings), “F” (forms), “B” (buttons), and “G” (graphics) to jump to specific elements.

We aim to support the widest array of browsers and assistive technologies as possible, so our users can choose the best fitting tools for them, with as few limitations as possible. Therefore, we have worked very hard to be able to support all major systems that comprise over 95% of the user market share including Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Apple Safari, Opera and Microsoft Edge, JAWS and NVDA (screen readers).

Despite our very best efforts to allow anybody to adjust the website to their needs. There may still be pages or sections that are not fully accessible, are in the process of becoming accessible, or are lacking an adequate technological solution to make them accessible. Still, we are continually improving our accessibility, adding, updating and improving its options and features, and developing and adopting new technologies. All this is meant to reach the optimal level of accessibility, following technological advancements. For any assistance, please reach out to